Eager to engage concertgoers at large venues, Queen recorded an audience-participation song for its sixth studio album, “News of the World.”

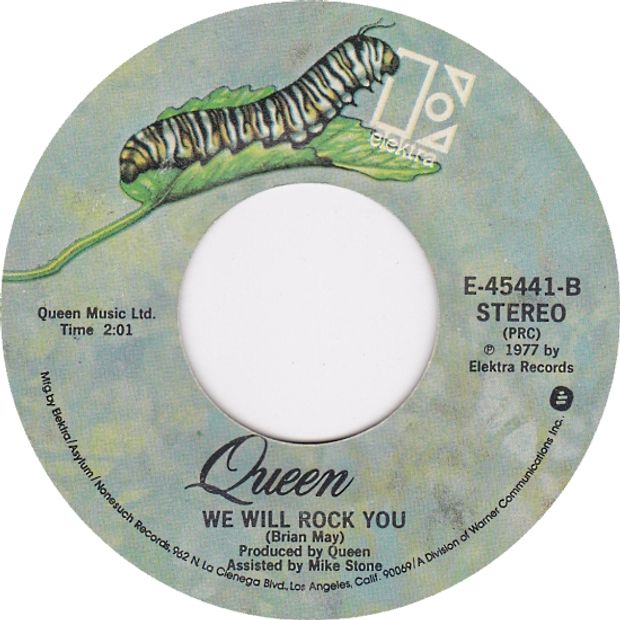

Released in October 1977, “We Will Rock You” opened the album, followed by “We Are the Champions.” After the two songs began to be played as one on the radio, the single featuring both reached No. 4 on the Billboard pop chart and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2009.

Recently, Brian May, Queen’s lead guitarist and composer of “We Will Rock You,” recalled the making of the hit. Queen’s new album, “Live Around the World,” with singer Adam Lambert, is due on Friday. Edited from an interview.

Brian May: During the start of our British tour in early ’77, audiences were pretty quiet. They might tap their feet but they didn’t participate. They just listened and made a big noise at the end. Singing along was still considered uncool.

But as our tour progressed, we noticed something odd. Audiences were singing. At first we sort of felt they should keep quiet and listen to what we were playing.

Then one night in May, at a big cowshed of a place called Bingley Hall in Stafford, between Birmingham and Liverpool, the audience sang along to all of the songs we played. We kind of laughed about it. At the end, as we waited off-stage before going back on for our encore, the audience broke into “You’ll Never Walk Alone.”

The song was and is an endearing anthem sung by fans of the Liverpool Football Club before each home-stadium match. Hearing such a revered song sung for us was emotional, since it was spontaneous. When we went back out, they were still singing.

Queen in 1978: from left, Roger Taylor, Brian May, Freddie Mercury and John Deacon.

Photo: Richard E. Aaron/Redferns/Getty Images

After the concert, the four of us—me, Freddie Mercury, Roger Taylor and John Deacon—talked about the audience’s growing role at our concerts and why it wasn’t such a bad thing. That night, back at the hotel, I thought about the audience and started writing a song. It would let them engage with us by singing, stamping their feet and clapping. It also needed some sort of a chant. In my head, I heard, “We will, we will rock you.”

I wrote three verses by singing them into my small hand-held cassette tape recorder. I had this story in my head about the power of a person as he or she ages. The three verses would be the three stages of life—childhood, young adulthood and old age.

The first verse was about being a kid wondering if you’re going to make a mark in the world:

“Buddy, you’re a boy, make a big noise / Playin’ in the street, gonna be a big man some day / You got mud on yo’ face / You big disgrace / Kickin’ your can all over the place.”

As a young adult, we feel the power we have, we get angry about things and we try to change them:

“Buddy, you’re a young man, hard man / Shoutin’ in the street, gonna take on the world some day / You got blood on yo’ face / You big disgrace / Wavin’ your banner all over the place.”

And the last verse was about old age and acceptance. By then, you have to pick and choose your fights to maximize your effect:

“Buddy, you’re an old man, poor man / Pleadin’ with your eyes, gonna make you some peace some day / You got mud on your face / Big disgrace / Somebody better put you back into your place!”

It’s the evolution of someone who wants to change the world, who never quite gets a handle on his rage but learns to live with it. It’s what you dream of and hope for and the frustration you face. In my songs, there’s always an element of irony.

“We will, we will rock you” is a cry, full of surety and confidence, that we will rock everything. But it’s also the realization that our power is limited. Chanting “We will rock you” is fortifying but, in the end, we realize how little power we actually have. Once you admit you’re powerless, you’re motivated to find a higher power.

I sang all of this into the tape before going to bed. The next day, I didn’t change much, but I was a bit nervous about bringing it to the band.

When I listened back, I worried it sounded too simple and obvious. Eventually, I sang it for Freddie. As I sang the lyrics, I watched his face.

Freddie was nodding slowly and sagely. It was hard to know what he was thinking. Freddie was instinctive, not analytic. More than likely, he was figuring out whether he could make something of it.

When I finished, Freddie said, “I like this, I like this, let’s try it.” As the drummer, Roger had some reservations at first, since there wouldn’t be drums on the track. Instead, I envisioned the song just with vocals and percussion by the band. It had to be an audience-artist, push-and-pull thing.

Share Your Thoughts

What’s your pick for the best-audience participation rock song of all time?

That summer, we went into Wessex Sound Studios, a large space in St. Augustine’s Church in London. First, we recorded the rhythmic stamps and claps I wanted for the song’s foundation. I had already come up with the “bump-bump clap, bump-bump clap” rhythmic pattern. I envisioned something simple audiences could do while standing, jammed tightly together.

But there was a problem. We couldn’t get the stamping sound I wanted out of the studio’s floor. So I looked around. In a corner, someone had left a dozen or so wooden boards used to support a drum riser. I went over and stamped on them. They sounded great. I dragged the boards a few feet into the middle of the studio, and we had them mic’d up. The church hall was a big space with high ceilings and a lovely natural echo.

I arranged the boards haphazardly. I wanted them to be uncontrolled when we stamped hard. When we did, they chattered and stopped. They didn’t resonate, giving the sound a lovely shortness.

Freddie Mercury and Brian May, far left, in Inglewood, Calif., in March 1977.

Photo: Armando Gallo/Getty Images

We ran tape, and stamped and clapped. It took about an hour to record 50 different takes, building up a compilation. This gave us the multiple versions needed for the effect. I wanted the sound to feel as if a large audience was all around you, stamping and clapping. There’s no echo on the song to create that effect, just multiple delays—a repeating technique.

When Freddie, Roger and John heard the song’s punch developing, they became more confident in the song. So did I.

Next, we turned to recording the background vocals on the chorus—“We will, we will rock you.” To make us sound like the audience, we sang it numerous times. Again, I added delays at different intervals.

Then Freddie went into the studio and sang two or three takes of his lead vocal. He was instinctive and full of passion. You can hear it in his voice. He was tearing himself up, no holds barred.

Freddie sang it a little differently from my demo, but kept the essential spirit and added his own touches. Once I heard his version, all doubts about the song disappeared.

Then I overdubbed a guitar solo. I used my Red Special guitar that I built with my dad in the ’60s with wood from an old fireplace mantel. My solo hinged on a four-string A-chord with the second, third and fourth strings an octave higher than normal. What you hear is the low and high strings interfering with each other, especially coming through my Vox AC30 amp. You get this wonderful, smooth ride into distortion, like a human voice going into overdrive.

For the guitar solo, I improvised three different takes and kept the bits I liked. I also liked one of my short repeating motifs at the end. So I copied the motif twice and we spliced it onto the tape. That’s what you hear at the wind-down of the solo.

But I didn’t want to place the solo in the middle of the song. I didn’t want to interrupt the flow of the chanting, stamping and clapping. Instead, I placed it at the end. I wanted to be part of the live action, like a director appearing suddenly in his movie. It was my signature, something I could perform in concert after the audience had done its part.

We lost Freddie in 1991. I miss him every day, especially his wicked sense of humor. He was great fun to be with.

Today, what I love most about the song is that people think it’s traditional, that no one wrote it and that it’s been around forever. To me, that’s the greatest compliment of all. It makes me feel empowered.

Copyright ©2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved. 87990cbe856818d5eddac44c7b1cdeb8