Advertisement

The Rush drummer and lyricist known for his intricate yet explosive playing has died at 67.

By Christopher R. Weingarten

Neil Peart, the drummer and lyricist for the Canadian prog-rock band Rush for more than 40 years, died on Jan. 7 at 67. Regarded as one of the greatest rock drummers of all time, he combined virtuosic technical ability, arena-filling intensity, exacting precision and enough restraint to endure as a constant presence on FM radio.

To drummers in the ’70s and ’80s, Peart was an Eddie Van Halen figure, someone whose pyrotechnic chops seemed to be the ne plus ultra. Peart never shied from flashy soloing or tom-tom blitzkriegs on his massive kit, yet he was also a master of discipline whose steady but tastefully punctuated grooves propelled “Closer to the Heart,” “Tom Sawyer” and “The Big Money” to the Billboard Hot 100.

By the 1990s, a generation of drummers influenced by Peart had turned chops and bluster into platinum success, among them Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Stephen Perkins of Jane’s Addiction, Tim “Herb” Alexander of Primus and Mike Portnoy of Dream Theater. As his own career progressed, Peart absorbed inspiration from new wave, jazz, bossa nova and African music, and — though an untouchable giant on the kit — still took lessons into the ’90s and ’00s from jazz musicians including Freddie Gruber and Peter Erskine. Rush remained a massive concert draw until its final show in 2015.

Here are 10 essential tracks from rock’s beloved rhythm scientist.

“He comes in, this big goofy guy with a small drum kit, and Alex and I thought he was a hick from the country,” the Rush frontman Geddy Lee recalled in The Guardian of Peart’s tryout for the band. “Then he sat down behind this kit and pummeled the drums — and us. As far as I was concerned he was hired from the minute he started playing.”

After Peart, then 21, joined Rush, its sound evolved from the spirited hard rock of its 1974 self-titled debut to the complex, skittering power trio that pioneered the space where heavy metal thunder meets prog-rock ostentation. Peart’s hectic drum style was influenced by U.K. busybodies like the Who’s Keith Moon and Cream’s Ginger Baker; his lyrics were informed by the individual-minded writings of Ayn Rand and the fantastical worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien. On the opening track of “Fly by Night” from 1975, Rush’s first album with Peart, he begins with guns blazing, tick-tacking through a 7/8 riff. Throughout, Peart embellishes with snare flurries and splash cymbal accents, ending with a precise tumble through his toms.

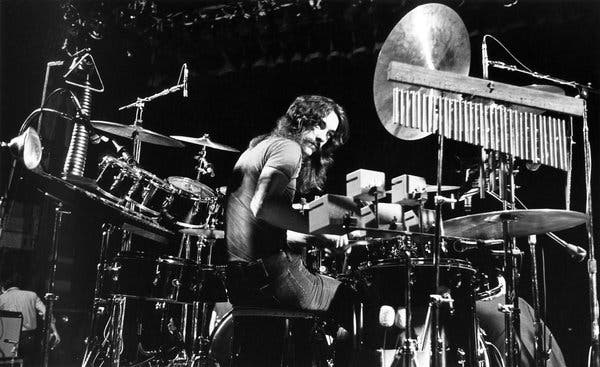

Peart’s highly technical drum solos were an essential part of the Rush live experience. On its first live album, “All the World’s a Stage” from 1976, Peart puts his manic signature on two songs that Rush released before he was in the band, then bursts into a jazz-flecked snare workout. For nearly three minutes on the fourth side of this double LP, Peart runs circles around his kit: eight toms, two splash cymbals, four cowbells. A simple ostinato for his four limbs — hand-hand-foot-foot — turns into a tornado.

As Rush’s ambitions expanded, so did Peart’s kit. The dynamic and orchestral “Xanadu,” the 11-minute opener of the band’s fifth album, “A Farewell to Kings,” naturally features Peart’s tom explosions alongside the band’s unpredictable shifts in rhythm. But “Xanadu” is also notable for more austere portions where Peart emotes like a one-man orchestral percussion section, working through wooden temple blocks, wind chimes, tubular bells, glockenspiel, a bell tree and tuned cowbells. Based on the famous Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem, Peart described the song in the program for the band’s 1977-1978 tour as “certainly the most complex and multi-textured piece we have ever attempted.”

“Yes, it is an indulgence,” Geddy Lee told The Guardian about this 12-part suite, “but it seemed to be a pivotal moment for us in creating a fan base that wanted us to be that way.” Subtitled “An Exercise in Self-Indulgence,” “La Villa Strangiato” features the band traversing multiple moods in nine minutes and 30 seconds: Spanish guitar, synth-heavy space-prog, jazz fusion, an interpolation of Raymond Scott’s “Powerhouse” (which you would likely know from many Looney Tunes shorts) — all of which Peart handles with aplomb. “There’s also a big band section in there,” Peart told CBC Music, “which was absolutely for me because I always wanted to play that approach.”

“‘The Spirit of Radio’ is a valid musical gumbo, even now,” Peart told Spin in 1992. “The concept was to combine styles in a radical way to represent what radio should be.” Peart has said his playing was influenced by reggae, new wave and punk, but the intro and breaks here are pure Peart insanity.

With its four-times platinum eighth album “Moving Pictures,” Rush mastered a paring down from multipart suites to lean rock songs. Though it features a 7/4 interlude, “Tom Sawyer” is relatively straightforward, but still an air-drumming classic. Opening with a wide-open breakbeat and a Oberheim synth glurp, Peart’s beat became irresistible sample fodder for rappers like Mellow Man Ace and Young Black Teenagers, and an integral part of the routines of chops-heavy turntablists like DJ QBert and Mixmaster Mike.

On its second live album, “Exit … Stage Left,” Rush uses its most infamous piece of rhythmic trickery: The 5/4 riff of “YYZ” is the code for the Toronto Pearson International Airport rendered in morse. Here it meets one of Peart’s heaviest drum solos: His snare is an out-of-control locomotive. He pingpongs in the high reaches of his eight toms and indulges in some Gene Krupa-style big band stylings while simultaneously clanking a melody line on his cowbells. Peart also an early adopter of the rumbling gong bass drum — a giant drum mounted like a tom-tom — eventually embraced by bands including Dream Theater, Primus and Korn.

Speaking about his lyrics, Peart told Rolling Stone, “A lot of the early fantasy stuff was just for fun. Because I didn’t believe yet that I could put something real into a song.” That is, until he wrote the 1982 restless suburban lament “Subdivisions.” “From then on, I realized what I most wanted to put in a song was human experience,” he said. The track once again features a masterful use of 7/8 and explosive fills.

After his daughter died in a car accident in 1997 and his partner succumbed to cancer less than a year later, Peart left music and traveled around North America on his motorcycle. He returned in 2001 and Rush’s subsequent album “Vapor Trails” was one of its most rock-centric in years — its first without a keyboard since 1975. The opener “One Little Victory” was the merciless lead single, starting with Peart playing what sounds like a rockabilly groove eaten by a thrash-metal monster.

In the mid-90s Peart felt his drumming was too metronomic, so he took lessons with the jazz drummer Freddie Gruber to loosen up his limbs. In this eight-minute drum solo from Rush’s fifth live album, you can hear a matured Peart focused on improvisation, playing out of the pocket, utilizing silence and culling melodies from his toms. “To me, drum soloing is like doing a marathon and solving equations at the same time,” Peart told Music Radar.