Remembering Jackie Shane, David Berman, Harold Bradley, busbee and more

Jackie Shane

Transgender soul pioneer

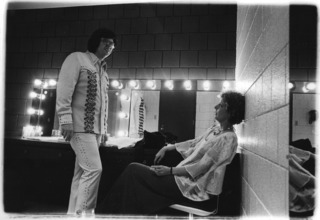

Jackie ShanePhoto: Mark Christopher

Jackie ShanePhoto: Mark Christopher

On Feb. 21, beloved soul singer and Nashville native Jackie Shane passed away in her Salemtown home at age 78.

Shane began performing soul and R&B music in and around Nashville in the 1950s, playing clubs like the famed New Era. She was briefly part of Excello Records’ studio band, but in 1961 she fled the Jim Crow South to Toronto, which would be her home for the next decade. In 1971, she walked away from music, settling in Los Angeles for a time with her mother and eventually returning to Nashville to live a solitary life. It wasn’t until the 2017 release of her Grammy-nominated Numero Group career retrospective Any Other Way, which compiles most of her known recorded work, that Shane was heard from again.

In addition to her music, Shane was known for living the majority of her life as an out transgender woman. In a 2018 interview for the Scene’s annual Pride Issue, Shane told me: “Even those who, at first, would wonder about me — well, I’m a human being just like you are. We’re all different. And that is the wonder of it all. It’s a beautiful thing. Can you imagine if we were all the same? Oh, please, the world is boring enough.”

Shane was reluctant to participate in interviews and gave only a handful in support of Any Other Way. Once you won her trust, though, she was warm, gregarious and willing to speak at length and with great enthusiasm about her remarkable life. She was also quick to dispense her hard-earned wisdom.

“My slogan is to live and let live,” she told me. “There’s no one on this planet that knows the secret of it all. It’s been that way from the beginning, and it will be that way when it ends. We’re in the greatest mystery ever, the mystery of life. We simply do the best we can, and march on.” —Brittney McKenna

Harold Bradley

Guitarist, studio owner, envisioner of Nashville’s future

Guitarist and studio owner Harold Bradley helped define country music as pop in Nashville during the 1960s. In the current era of syncretic pop-country crossover, this may seem like a foregone conclusion. But Bradley’s understated guitar work — he was a self-taught player who began appearing on the Grand Ole Opry in 1946 — turned away from old-time country, and pointed the way to the future.

Bradley was born in Nashville on Jan. 2, 1926. He toured with Ernest Tubb when he was a teenager, served in the Navy, and played on Red Foley’s 1950 hit record “Chattanoogie Shoeshine Boy.” In 1954, he and his brother Owen started the Quonset Hut Studio on 16th Avenue South. He played on many of the hits cut there, including Patsy Cline’s 1961 “Crazy” and Tammy Wynette’s 1968 “Stand by Your Man.” He was also part of the group who built another famous Nashville recording studio, RCA Studio A.

Bradley’s work transcends the so-called countrypolitan label, but what he and his brother envisioned for Nashville was, at its core, pop success. He imagined the future, and liked what he saw. Earlier this year, Belmont University established a scholarship in Bradley’s honor — the Harold Bradley Endowed Scholarship, which will be awarded to freshman guitar students in the school’s College of Visual and Performing Arts. Bradley died in Nashville on Jan. 31 at age 93. —Edd Hurt

Melva Clarida

Renaissance woman

Melva Clarida with Ronnie MilsapPhoto: Courtesy Mark Linn

Melva Clarida with Ronnie MilsapPhoto: Courtesy Mark Linn

I didn’t meet Melva Clarida, who passed away in February at age 81, until 2015, but I’d been searching for her for more than a decade. From 1963-1977, she made an indelible mark on Nashville during its artistic renaissance, then packed up and left without a trace.

Melva’s roles included: serving as assistant to education pioneer Susan Gray, who founded Nashville’s Head Start program; associate producer on The Johnny Cash Show; and manager of Charlie Pride, Ronnie Milsap, Ian Tyson and Marshall Chapman. Whip-smart, funny and revered, Melva had the ability to stand out and blend in amid a town full of good ol’ boys.

In 1967, Melva moved to the small town of Kingston Springs with her then-husband, songwriter Vince Matthews. Their home became a refuge for struggling Nashville songwriters, as well as future legends Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash, Townes Van Zandt and Patti Smith. Music and food were plentiful, as was a homemade corn-cob wine that would be immortalized in song by Vince. Johnny Cash described the song “Melva’s Wine” as “the greatest contemporary American folk song I’ve ever heard.” Their life in Kingston Springs, the town’s history and people, and fear of the old ways disappearing in the name of “progress” inspired a concept album, The Kingston Springs Suite. Produced in 1972 by Shel Silverstein, Kris Kristofferson and Cowboy Jack Clement, it was the toast of the Nashville outlaw underground, then mysteriously shelved for more than 40 years. Once I heard the album, I was determined to release it on my label Delmore Recording Society — and to locate Melva.

In a strange turn of events, it was Melva who found me, in 2015 when she purchased a copy of the newly released record from the label’s website. Meeting her shortly thereafter was an otherworldly experience. Besides regaling me with stories about Vince and their adventures with all kinds of folks (from Kris, Shel and Cash to Nelson Algren, Lanford Wilson and Howlin’ Wolf), Melva also handed over a bin stuffed with reel-to-reel tapes, slides and incredible photos — many of which she had taken and developed herself. We talked for hours about that golden era in Nashville, why she left, and where she’d been for so many years. We kept in touch, and plans were hatched for radio interviews, a program at the Country Music Hall of Fame and a book — but time got away from us. Four years later, she’d be gone. —Mark Linn

Mac Wiseman

Musician, International Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, Country Music Hall of Fame inductee

“The Voice With a Heart” is what they called Mac Wiseman, and listening to his warm, reedy timbre, distinctive enunciation and gliding, almost effortless phrasing, it’s easy to see why. That voice served him well in a career that spanned more than 70 years, prior to his death in February at age 93. It began with him playing bass with Kentucky gospel singer Molly O’Day and included late-’40s stints with Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys (he was a founding member) and Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys before he made his first records as a frontman in the spring of 1951.

From the beginning — whether he was on his own or collaborating with musicians as varied as Woody Herman, Doc Watson, Del McCoury, The Osborne Brothers and John Prine — Mac was instantly recognizable. No matter the song, he always sounded like he was fully invested in its essential emotion. Not only that, what was true at the start was no less true when he made his last recording 65 years later. Fittingly enough, it was a reprise of his first big hit, “ ’Tis Sweet to Be Remembered,” sung with Alison Krauss.

But Mac was more than a musician. Besides recording for Dot Records, he did A&R work for the label; he was a founding member of the Country Music Association; he ran his own festival in Kentucky for years; and he served as secretary-treasurer for Nashville’s Local 257 of the American Federation of Musicians. He was about as rooted in both music and the music industry as a person can get. He was generous with his time, and both wide-ranging and exacting in his views of bluegrass and country music and their connections to the larger musical world. He kept his sly sense of humor and earthy sentimentality to the end. Mac Wiseman had a good long run, and the music in which he was such a durable presence is all the better for it. —Jon Weisberger

Michael James Ryan Busbee

Producer, songwriter, beloved collaborator

The working relationship that Maren Morris shared with producer and songwriter Michael James Ryan Busbee, professionally known as busbee, created a type of magic that simply can’t be duplicated.

Every song on Morris’ hit debut 2016 LP Hero was either produced or co-written with the California native, who helped cultivate her trademark sound that travels across genre lines. They continued to evolve together, bringing an elevated sound to Morris’ 2019 follow-up record Girl, which featured busbee’s production on 11 of its 14 tracks. Just weeks after he and Morris were nominated for Album of the Year at the 2019 CMA Awards, busbee passed away Sept. 29 from glioblastoma, an aggressive form of brain cancer. He was 43 years old.

Along with his extensive work with Morris, busbee co-wrote Garth Brooks’ 2014 comeback single “People Loving People,” Florida Georgia Line’s “H.O.L.Y.,” Carly Pearce’s “Every Little Thing,” and Keith Urban and Carrie Underwood’s hit collaboration “The Fighter.” He also worked closely with Lady Antebellum, producing multiple tracks on their record 747 and all of their 2017 LP Heart Break. Outside of the country realm, busbee found plenty of success in pop, with co-writes recorded by Pink, 5 Seconds of Summer, Kelly Clarkson, Christina Aguilera, Toni Braxton and the Backstreet Boys.

The meshing of Morris’ soulful, colorful vocals and busbee’s ability to perfectly blend elements of country and pop resulted in a sound that connected with millions. The loss of busbee’s keen creative ear is an immeasurable blow to Nashville and the industry as a whole. He left behind a body of work that changed country music, and music as a whole, for the better. —Lorie Liebig

Jim Glaser

Country singer and songwriter, member of The Glaser Brothers

In 2012, I asked Jim Glaser to talk to me about recording with Cowboy Jack Clement in the ’60s. I had seen him perform recently, and I was pleased to learn he had kept his vocal chops in top shape. He agreed to the interview, showing up precisely on time. He told me about working with Clement, and he also talked frankly — and a little bitterly — about his ’80s Nashville record label, which he said hadn’t promoted his best work. It was a lesson in music-business reality.

James William Glaser was born on Dec. 16, 1937, in Spalding, Neb. With his brothers Tompall and Chuck, he came to Nashville in the late ’50s, recording with country star Marty Robbins — that’s Jim nailing the high tenor part on Robbins’ 1959 recording of “El Paso.” A sharp and prolific songwriter, he co-wrote the pop standard “Woman, Woman,” a 1967 hit for Gary Puckett and the Union Gap. On his own after The Glaser Brothers dissolved in 1982, Jim went in a different direction than Tompall, who had veered into country-funk. Jim cut a series of songs that embody country-pop romanticism, including “You’re Gettin’ to Me Again” from 1983, and 1986’s exquisite “The Lights of Albuquerque.”

Glaser retired from music for decades, but returned to publish a novel about the music business, 2013’s Drowning on the Third Coast. That year Tompall died, a few days after Clement. Until the end, Jim remained a first-rate singer who could angle his precision instrument to an exact point in the sky. He died April 6 at his home near Nashville at age 81. —Edd Hurt

David Berman

Songwriter, poet, illustrator, leader of Silver Jews and Purple Mountains

David Berman (self-portrait)

David Berman (self-portrait)

I got to be friends with David Berman around the time of the Bright Flight sessions in 2001. I was barely of legal drinking age, but even back then he and his wife Cassie and their whole crew took me in without any precious sense of me not “belonging,” or being the kid. David hated being called “Dave,” and nicknames in general. He joked that, “You can’t call me Dave, it’d take away my ‘id.’ ” So he very graciously never called me “Willy” — only William. I had no business being in that session at that time, but he gave me a chance, and I am so grateful. It was a painful time — lots of hard living, drugs and things that made me feel a lot younger. Sept. 11 had just happened, and the existential darkness was similar to now. The music, of course, was brilliant and painful.

I saw David and Cassie only intermittently until 2006, when the live incarnation of Silver Jews took flight for three glorious and chaotic years. Apart from just being grateful for the experiences I had with them — from playing Tel Aviv to playing a cave in McMinnville — being around David was a master class in wit and wise observation. He’s the only person I’ve ever been in a band with who read as voraciously as me. The van was littered with heavy books that we would unpack on long drives.

His words and his songs meant a lot to me, but they meant an incalculable amount to people he never met, and some he only fleetingly met. He always made time for fans after shows — he was very gracious and generous with his time. He told me he didn’t want his persona to be difficult or hard-to-approach. I think that represented a kind of friendly humility that he admired in country music stars as well.

I feel like I could write a book out of the anecdotes we all shared together, and I can barely fathom the pain that those closest to him feel in the wake of his suicide at 52. But his life and his work burned with a righteous fury that is growing scarcer by the day in our climate of short attention spans, memes and quickly moving on to the next thing. I’m glad he was able to grace us with one more record, Purple Mountains, before he sailed his ship to the other shore. I am sad that I won’t ever be able to share stories with him in this world, but I am truly grateful that we got to share some real estate and camaraderie for a time. —William Tyler

Lushene Holt

Punk apostle

Lushene Holt (aka Lushene Holiday, because she wanted every day to be a holiday), who died in May at age 62, was a fixture of the early Nashville punk scene in the 1980s. She wasn’t in bands, but wherever you’d find public displays of transgression, you’d find her. In the pre-internet age, she was an encyclopedia of difficult-to-find, absolutely batshit-crazy material.

Many of us crafted our eccentricity into provocative and irritating musical projects. For others like Lushene, uncompromising weirdness only offered up concerned parents, bounced-check notifications and spectacular drug escapades. I hadn’t talked to her in a long time, but she regularly sent me incomprehensible messages at 3 a.m.: odd video clips, waves, emojis of snowmen, dancing wolves, ray guns. I like to think she was just reminding me that she was still out there, denying the man another soul to commodify. —Dave Willie

Reggie Young

Session guitar legend

Reggie Young, who died in Leiper’s Fork on Jan. 17 at age 82, played guitar on a huge number of recordings that have become country, pop and soul classics. Young added his fluid licks to Dusty Springfield’s 1969 album Dusty in Memphis, and he played on sessions with Elvis Presley, Joe Tex, James Carr, Billy Swan and Dobie Gray. Many of Young’s best-known recordings feature a lick, invented by Young, that defines the performance. Like his fellow Memphis rhythm-guitar masters Teenie Hodges and Bobby Womack, Young was a structural thinker.

Young was born Dec. 12, 1936, in Caruthersville, Mo. He made his name in pop and country, and he lived and recorded in Nashville for decades. But I like to think of him as a quintessential Memphis musician. Like Hodges, who devised unforgettable licks for records by Al Green and producer Willie Mitchell, Young knew how to lay back in a rhythm section. You can hear his restraint on an obscure 1967 Willie Mitchell record, “Mercy,” in which Young plays strict rhythm guitar behind Memphis ax man Clarence Nelson’s brief, stinging lead.

I saw Young demonstrate some of his signature inventions at a 2008 program at the Country Music Hall of Fame. He played his intro to Swan’s 1974 track “I Can Help,” and he made it look easy. For Young, it was about the total effect — he never showed off, because he didn’t have to. —Edd Hurt

Scott Ballew

Powerhouse drummer, devoted friend

Scott BallewPhoto: Moneypenny, courtesy Steve Ballew

Scott BallewPhoto: Moneypenny, courtesy Steve Ballew

If you ever saw Scott Ballew onstage with our band The Shazam — looking like a blond surfer dude and casually raising hell on the drums like some ’60s English rock god, and having a hilarious time doing it — well, that was pretty much what you got if you knew him. Affectionate like a big puppy.

If he wasn’t playing drums, he was still giving “210 percent” to whatever he was doing — never half-assing anything, never boring, always capable, funny as hell and eternally youthful. He was all about getting it right the first time. When imbibing, he was a force of nature. “Hard Charger,” as he would say. That especially applied to the way he played the drums.

But he really was a rock god, on every level. Once we were in a bar and some amateurish young band was struggling through some classic-rock staple. Scott jumped up onstage, took the sticks from the drummer, shooed him away and rocked them to a glorious finish. And they thanked him for that!

Scott always joked that he was my muse, saying, “Every time you get mad at me, you write a good song.” Even after enough setbacks to give our band not much reason to continue, we did it anyway, because it was like breathing. Because even if it was just rocking out in a basement room, it was an essential part of our being and feeling alive.

We played together for 28 years. “Windmill in a tornado” was how he described it. In all the time I knew Scott, until his death in April at age 46 — I don’t think he ever failed to turn a spark into a mushroom cloud. Scott always provided the energy, the confidence and the enthusiasm, with a most absurd sense of humor and adventure. I can’t imagine anyone better to dream the dream with, to go after it with, to actually live the dream with. Godspeed, Scott Ballew. —Hans Rotenberry

Russell Smith

Songwriter and singer, The Amazing Rhythm Aces

Songwriter and singer Russell Smith was born in Nashville on June 17, 1949, and died July 12 in Franklin. He was in his early 20s when he wrote a song that defined his subsequent career. Smith’s “Third Rate Romance,” which appeared on his band The Amazing Rhythm Aces’ 1975 album Stacked Deck, may seem to belong to the ’70s. After all, that was the decade of NRBQ and Steely Dan — groups that drew from jazz, soul and rock ’n’ roll in ways that may sound dated in the current era of modern country and Americana.

Like, say, NRBQ, The Amazing Rhythm Aces came across as expert revivalists who harked back to the old ways. The group referenced Memphis soul on their ’70s records, but Smith’s work looked forward to today’s Nashville, where revivalism and soul aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. While the band’s later albums were engaging, Stacked Deck — cut at Memphis’ Sam Phillips Recording Studio — remains its testament.

In later years, Smith wrote country hits and played the occasional show in Nashville. I saw him a couple of times, and he came across as sly and sharp as he did on “Third Rate Romance.” A supremely relaxed performer, Smith looked like he knew the secrets of songwriting, and maybe a few others as well. —Edd Hurt

Jerry Carrigan

Masterful drummer, country music innovator

The history of Nashville music is inextricably tied to the innovations of Alabama, Memphis and New Orleans musicians. Drummer Jerry Carrigan took the approaches of New Orleans drummers like Earl Palmer and Charles “Hungry” Williams and applied them to country music. Along with Palmer and James Brown’s drummers Clyde Stubblefield and John “Jabo” Starks, Carrigan was a master of shuffle rhythms. He knew how to create excitement in a basic shuffle by dotting eighth notes or favoring a triplet feel, and he was a powerful player who experimented in the studio.

Jerry Kirby Carrigan was born in Florence, Ala., on Sept. 13, 1943. He played on the first major record to come out of the Muscle Shoals area, soul singer Arthur Alexander’s 1961 hit “You Better Move On.” Carrigan also laid down the groove on another foundational soul tune cut in Muscle Shoals, Jimmy Hughes’ 1964 “Steal Away.” In 1965 he moved to Nashville, playing on Charlie Rich’s epochal rock ’n’ roll hit “Mohair Sam” that year.

Carrigan’s Nashville work is notable for its vigor, and his snare-drum sound was loud and commanding. In Nashville, he worked with greats like George Jones and Dolly Parton. It was clear he never forgot the lessons he’d learned from listening to Palmer and Williams. Carrigan died on June 22 in Chattanooga at age 75. —Edd Hurt

Maxine Brown

Legendary country singer

I imagine Maxine Brown rising from the grave and looking over my shoulder to make sure I’m getting all her credits right. She was that kind of presence — proud, persistent and commanding — during the years we worked together on her memoir. Maxine, who died Jan. 21 at age 87, was the oldest and last remaining member of The Browns, a vocal trio that included her younger brother and sister, Jim Ed and Bonnie. Having worked the Louisiana Hayride and toured with Elvis Presley, they were already well-known when they hit the jackpot in 1959 with “The Three Bells.” The record spent 10 weeks at No. 1 on the country charts, four on the pop and even reached No. 10 in the R&B rankings.

The Browns scored their first hit “Looking Back to See” in 1954, a song Maxine and Jim Ed co-wrote. It also became the title of Maxine’s memoir, published by the University of Arkansas Press in 2005. The Browns disbanded in 1967. Maxine released a solo album in 1969, but it failed to attract much attention, leading her to retire from performing and become The Browns’ de facto chronicler. She was the inspiration for Rick Bass’ 2010 novelized account of the trio’s career, Nashville Chrome.

“That Maxine had a mouth on her,” her friend Bobby Bare declared when The Browns were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2015. She confirmed that assessment when accepting the honor. Leaning on a cane she used after a series of falls, she quipped that her surgeon was drunk when he put her broken bones back together. “The only good thing that came out of that,” she said, “was that I got a permanent screw.” —Edward Morris

Steve Sadler

World-renowned audio technician

Steve SadlerPhoto: Courtesy Randy Blevins

Steve SadlerPhoto: Courtesy Randy Blevins

People often think the creative geniuses in the music business are found only onstage, in high-rise offices or behind a recording console. Steve Sadler, who was 70 when he died in October, was proof that this notion is far from accurate.

From the 1960s to the ’80s, Florida-based Music Center Inc. made a popular line of recording consoles and analog tape machines, and Steve was one of MCI’s senior technicians. The company was sold to Sony and closed in the early 1990s. Steve took his deep knowledge of MCI equipment on a nationwide tour for several years, traveling in his van with his ragtag gang of pets, living in campgrounds and keeping recording studios humming all over the United States.

He settled in Nashville in the mid-1990s and let the work come to him via FedEx and UPS — and later, Skype. He could quickly fix any equipment that MCI had ever made, and was just as quick to remind you of that fact. He had a shop near The Fairgrounds Nashville and welcomed people from all over the world to visit, always taking time to show them his garden and his pets, and offering up his delicious homemade dishes. I can personally vouch that his lemon meringue pie was the best I’ve ever had. (Sorry, Mom!)

Simply put, Steve was the Rick Rubin of technicians. He dressed the way he wanted to dress, said what he wanted to say, and knew his shit so well that nobody could argue with him. Anyone with MCI equipment knew who he was and looked to him in times of need, because he could deliver the goods. He often appeared gruff to talk with at first, but it was all a ruse. He was not mean at all, but rather a quick-witted person with an oddly dry sense of humor that took some time for one to appreciate.

Steve’s contribution to the music industry is hard to measure. He mentored and taught everyone he met, and more recording sessions than you could count would’ve been scuttled had he not been on the case. Perhaps your favorite song would’ve never been recorded because a transistor or capacitor had failed the night before the session — only to be fixed by Steve Sadler in the nick of time.

His dedication to his craft was unparalleled. Even in his final hours, Steve was looking around his room at the Vanderbilt hospital, directing the many people who had gathered around him to work together to help repair something that had broken. Even though we knew this was a fictitious scenario being played out in his mind, we all “helped” the best we could, knowing that he was doing what he loved to do: troubleshooting and saving the day.

Godspeed, Steve. —Chris Mara

Kelley Looney

Bass player, songwriter, beloved bon vivant, food aficionado

Sunday morning, Nov. 3, I received a text from my godchild, Jennifer Herbert Pilkington, informing me that her brother Kelley Looney was in Vanderbilt’s ICU. It sounded serious, so I dropped everything and went to the hospital. The next morning I received another text that Kelley, age 61, had died.

Soon I’ll be 71 years old, so calls and texts of this nature are becoming commonplace. But this one hit hard. I later heard that Kelley’s last words were a song. He was singing: “What the world needs now is love, sweet love.”

Kelley was 14 when I first met him. (His mother, Betty Herbert, was the inspiration for my song “Betty’s Bein’ Bad.” But that’s a whole ’nother story.) Later, he’d be known for his long tenure in Steve Earle’s band, but from 1980 to 1982, he played bass with me on the road. Highlights of our time together included opening for (and backing) Big Joe Turner at the Lone Star Cafe in New York. Another: One night we were playing Cantrell’s here in Nashville, when Betty came waltzing in after driving back from her father’s funeral in Alabama. Next thing we all knew, Betty was standing on top of a table (in her pink linen dress and trademark pearls), waving a beer bottle, yelling “RAISE HELL IN DIXIE!” at the top of her lungs.

The first person I called after I heard Kelley had died was Fred Williamson Jr., who played lead guitar with us in the early ’80s. In the course of our conversation, Fred said: “Remember that time in Louisiana, when Kelley was dancing on top of that bar? He wasn’t doing it to show off or anything. It was just because he felt so good.”

Charles Kelley Looney lived life like it was a song. And it made us feel so good, we danced on tables. —Marshall Chapman

Bob Kingsley

Beloved country radio personality

For many singers, Bob Kingsley’s voice introducing their debut single on his syndicated countdown show made success official. Kingsley spent more than four decades behind the microphone of American Country Countdown and then Bob Kingsley’s Country Top 40, from 1978 until just days before his death Oct. 17, at age 80, of bladder cancer.

That voice, a mellifluous baritone, and his believability as he told the stories behind the songs, earned Kingsley a spot in the Country Radio Broadcasters DJ Hall of Fame in 1998 and the National Radio Hall of Fame in 2016, among many honors. But his legacy involved his kindness and affability as much as his talent. The word “beloved” kicked off the story of his death on AllAccess.com. “We lost a beautiful human,” added Keith Urban. Said Toby Keith, “I never met a nicer guy in my life.”

Kingsley, quarantined for a year with a childhood bout of polio, found escape and companionship in the radio shows of the 1940s. He was introduced to Armed Forces Radio while serving with the Air Force in Keflavík, Iceland, then landed a series of on-air jobs throughout the Southwest and Mexico. He worked at legendary L.A. stations KFOX, KLAC and KFI, and was named the Academy of Country Music’s Radio Personality of the Year in 1966 and 1967.

Kingsley was chosen in 1974 by Tom Rounds — who had founded a pop countdown show with Casey Kasem and wanted to do the same in country — as producer of American Country Countdown, and he took over as host four years later. The show quickly expanded to hundreds of stations and was named Billboard’s Network/Syndicated Program of the Year 16 times in a row.

Kingsley was a cutting-horse enthusiast who rode competitively into his late 70s, and a lover of fast cars and Western art. But it is as a lover of music and of the people who make it that he is remembered by those who knew him. —Rob Simbeck

Fred Foster

Hitmaker

In 1965, Fred Foster inked a young woman from Pittman Center in the mountains of Sevier County to a record contract for his Hendersonville-based imprint Monument Records.

“Sometimes, you just know — sometimes,” Foster said at his Country Music Hall of Fame induction in 2010.

He made very good use of his instincts with this particular 19-year-old. She scored two Top 40 hits with Monument, starting her on the path to icon status. Her name was Dolly Parton. Starting his own label gave Foster the opportunity to take chances when those instincts quivered. When he was a scout for Mercury in the 1950s, his pleas to sign a guy named Elvis Presley fell on deaf ears.

One Foster’s earliest — and most enduring — stars at Monument was, like Elvis, a Sun Records alum. Roy Orbison’s biggest hits were all on Monument, several produced by Foster himself. Foster also saw something in a Rhodes scholar and songwriter named Kris Kristofferson. Foster shares a writing credit on “Me and Bobby McGee,” and Combine Music, his publishing outfit, put out many of the now-iconic songs that flowed from Kristofferson’s pen. Combine also published “Polk Salad Annie,” “Rainy Night in Georgia” and Presley’s “Burning Love.”

Foster said he always wanted to make music that would endure, and as if the aforementioned tunes aren’t evidence he did that, search YouTube for the innumerable videos set to the Boots Randolph instrumental “Yakety Sax,” a Monument release in 1963.

Foster died in Nashville Feb. 20. He was 87. —J.R. Lind