In 2018, singer-songwriter Esmé Patterson had prepared a list of producers to help turn her latest batch of demos into “There Will Come Soft Rains,” her major-label debut. None were in Denver.

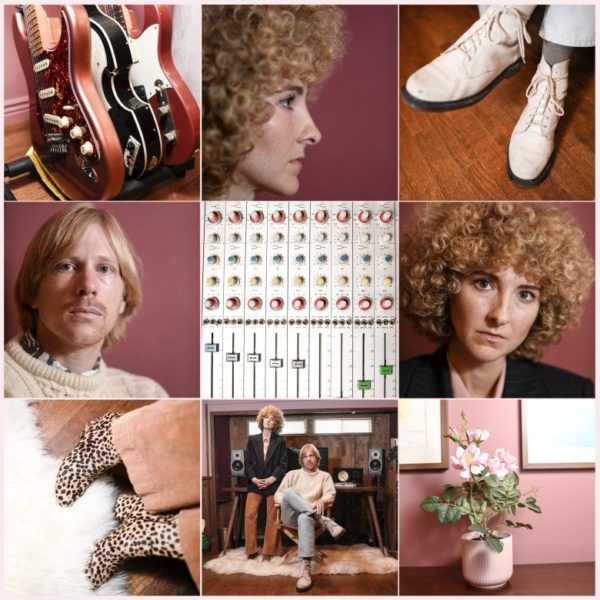

But then, an old friend reached out. Alaina Moore, a fellow Front Range native — and with her husband Patrick Riley, one half of indie-rock duo Tennis — noticed it had been awhile since Patterson’s last album, 2016’s “We Were Wild,” and asked if she had been sitting on demos. She was; they got to work.

“I definitely wouldn’t have made the record in Denver if not for Tennis,” Patterson said.

While Denver’s rock milieu has sprung some national artists, the scene’s industry — which crucially includes music production houses — lags behind that of comparable cities like Portland, Ore., and Austin, Texas. In part because, while based here, few of those acts have bought back into the local industry.

Mutually Detrimental, Tennis’ three-year-old record label, is changing that. While not the only high-level producers in town, the Tennis name holds national sway, giving our still-burgeoning rock music industry a rare asset: a shop that national acts will travel to Denver to work with.

“Tennis producing records here is important,” said Patterson, a Boulder-born music industry veteran who once joined Tennis live on “The Late Show with David Letterman.” “It lends a sense of credibility and an international gaze to what’s happening here musically.”

A music producer is to an album what a director is to a film, or an editor to a writer. They take raw, creative output and turn it into a cohesive whole, often putting their own spin on it.

To that end, Tennis has built its dream studio in the members’ Five Points garage, a testament to the decade-plus they’ve spent touring and recording with the likes of The Black Keys’ Patrick Carney, who produced the band’s sophomore effort, and the late Richard Swift, a mutual collaborator of Nathaniel Rateliff. The crown jewel is a Studer 269 mixing console, which they used on “Swimmer,” out Friday, Feb. 14.

“Lou Reed used it on several records,” Moore said.

So far, that studio has turned out a few singles, two EPs and two full-length records for artists across North America, including Nashville brother-duo Airpark, Vancouver’s Johnny Payne and the Los Angeles-based Beauty Queen.

If not for Tennis, the artists said in emails, none of these bands would have come to Denver to make an album.

“We were in town to work with Patrick and Alaina,” Airpark, whose Tennis-produced EP “Songs of Airpark” was released last February, said through a rep. “The fact that they live in Denver was a nice bonus.”

Denver artists are getting in on it, too. Aside from the duo’s self-produced “Swimmer,” two other Tennis-produced albums will see release in the coming weeks: Patterson’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” and Down Time’s “Hurts Being Alive,” both out March 6.

“It means a lot to be able to provide something in Denver that we had to go looking for in our early days,” Moore said. “I finally feel like we are at a place where we can stay put and apply what we learned and offer it back up to our hometown.”

For Patterson, that meant not having to book a costly trip out of town to cut her major-label debut.

Patterson spent “several years” trying to find the right producer for “There Will Come Soft Rains,” her fourth solo effort (she was a core member of Boulder folk group Paper Bird). That wasn’t an easy task, underscoring the sexism that pervades the world of production, a male-dominated arm of a male-dominated industry.

“Being able to make a record where one of the producers was a woman was a big thing, and being able to do that in Denver was wonderful,” Patterson said.

Patterson and Tennis cut the album in two weeks, a “whirlwind,” Patterson said, that produced one of her most proud pieces of work. “And it was very much a product of that collaboration with Tennis.”

They introduced her to Jim Eno, the drummer for Austin rock band Spoon, who’d mix the album.

“Just them working in Denver opens up different doors that wouldn’t be open otherwise,” she said.

That wisdom is of even more use to small local bands unknown outside of the Front Range. That was the hope that Denver’s own Down Time had when they cold-called the band’s manager in late 2018 to produce and mix its debut LP.

“It sounded like a crazy idea,” said frontwoman Alyssa Maunders. “We did not expect to hear back.”

But nine months later, they found themselves in Moore and Riley’s studio, hashing it out.

While it isn’t a magic bullet, having the Tennis name attached to a project is meaningful currency, one that factored in for almost every band interviewed for this piece.

But the band has as much to offer as a mentor as it does a cosign.

“The value of working with them wasn’t just in them cross-promoting us, but to be able to hear what they’d learned as they grew to their level,” said bassist David Weaver.

Working with a high-level producer may seem like a no-brainer for small bands, but it’s risky, both financially and creatively. Bands pay to put their songs in the hands of producers who may have a strikingly different vision for them. There are no right answers in art; collaboration is a sensitive dance.

Tennis experienced that first hand working with The Black Keys’ Patrick Carney, the first dedicated producer the band hired. Carney had argued for using an acoustic guitar on a song; Moore refused, insisting it reminded her too much of worship music. She relented, trusting him, and has since regularly incorporated acoustic guitar into their songs.

Down Time learned the same lesson. Over the course of the two years he’d been playing it, Weaver had grown attached to a bass line he wrote for the band’s lead single. Patrick had a different idea, one that lent more tension to the song.

It didn’t feel right in the moment, Weaver said, but he recorded it. After taking a walk, Weaver returned to the studio, and the Tennis-inspired bass line bloomed in his ear.

“All the songs were transformed by their process for the better,” Weaver said.

It was a full-circle moment for Moore, who remembered texting an apology to Carney.

“Now we’re the dad, the person saying ‘no’ or ‘trust me,’ and that’s painful,” she said. “It’s weird to be on the other side of things.”